Create Professional Martial Arts Lesson Plans

Lesson plans are the hallmark of a professional, skilled martial arts instructor. While many believe that they can teach class without one, their programs suffer from a lack of structure and focus, which eventually hurts the progress of their students.

If you want to consistently push your students to get better, and ensure that they have ample practice of the most important curriculum in your program, then you need to invest time in learning how to create excellent martial arts lesson plans.

In the article below, we explore how to approach lesson planning for martial arts classes and then offer some practical templates for you to use in your own planning process.

How to Create a Martial Arts Lesson Plan

Whether you’re an educator in a classroom or an instructor on the mat, lesson planning begins with a clear idea of what you want to accomplish with each lesson. To begin the creation of lesson plans, follow these 4 steps:

- Establish a session intention (learning objectives)

- Determine learning outcomes

- Gather practice exercises that support those objectives and outcomes

- Filter out suboptimal exercises and finalize the lesson plan

Establish a session intention

A session intention, also known as a learning objective, is a goal or a small number of goals that you want to accomplish through the lesson. Examples of session intentions might be “explore

Session intentions need to be specific enough to be useful but not so myopic that the lesson becomes boring. “Learn karate” is not specific. But “perfect chamber release on the spinning hook kick” is too specific, at least as the singular intention of the class.

The first is vague; the second is so specific that a 45-90 minute class on that subject would be boring, make everyone dizzy, and potentially lead to overuse injuries. If you want to include that as one of a few objectives, then it works. However, it’s important that a lesson does not have more than 2 or 3 learning objectives, because then it becomes unfocused and detrimental to learning.

Good session intentions/learning objectives might include:

- Slip punches to set up counterpunches

- Break the close guard

- Pass the open guard

- Low kicks to set up sweeps or takedowns

- Maintain full mount

- Escape side control

Determine learning outcomes

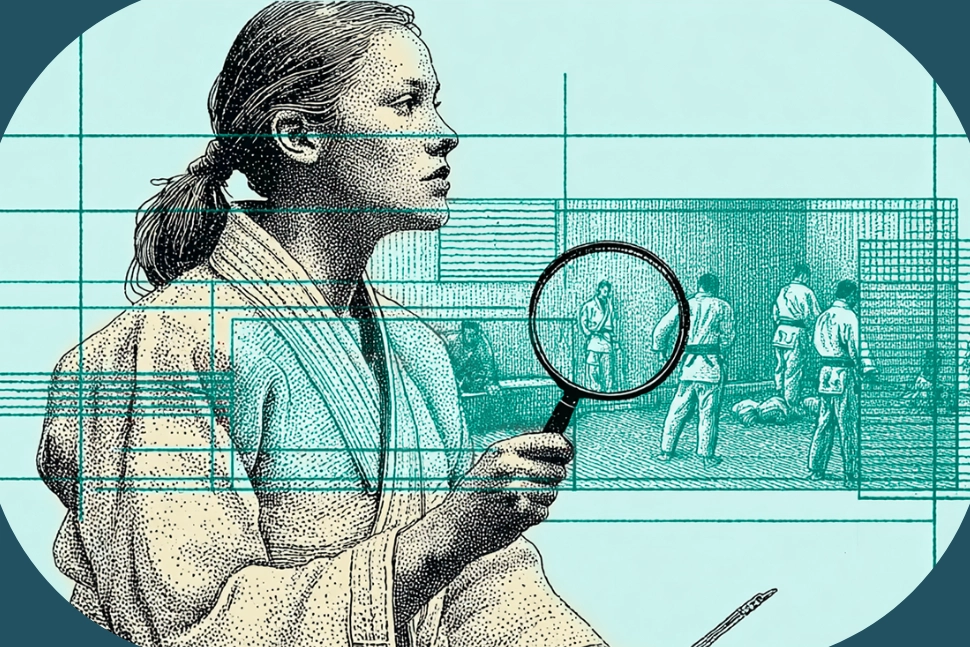

This step is more about setting expectations for yourself than for your students. You need a way to understand if your lesson plans are effective or not. So while it’s important to have a clear idea of learning outcomes, don’t become married to the idea that each lesson will be enough to cause those outcomes on their own.

A note for professionals: just because you have learning objectives and outcomes in mind doesn’t mean that you can reasonably expect to see them fulfilled after one training session. The scientific research warns us about the performance/learning paradox, where short term leaps in performance quality during class don’t necessarily equate to a permanent change in the quality of that skill.

In other words, it’s likely to disappear by the next training session. So adjust your expectations accordingly and be patient.

Gather practice exercises that support the session intention(s)

This step is a mind dump. Don’t worry about how effective a given practice activity is: if it might support the objectives you’ve set, list it down. The goal is to have the biggest inventory of relevant exercises to choose from in step 4.

With that said, as you get better at this process, steps 3 and 4 will blur together because you already have a sense of what exercises best support your goals and objectives, without much extra consideration. The added benefit is that it takes less time to complete this step, too.

Filter out suboptimal exercises and finalize the lesson plan

At this point, you begin to discriminate between the most effective and least effective exercises in your list. This filter is done by trying to match practice activities that best train for an objective to the time slot in the lesson plan for which that objective is being trained.

For example, let’s say one of your session intentions, or objectives, is to maintain side control. There are several exercises where you are challenged to maintain side control at some point, but the best exercise for that will involve something more like a positional sparring game where the game resets if the top player loses his side control.

The beauty of choosing the right practice exercises is that you can potentially hit multiple related learning objectives at the same time. With the example above, one player practices the objective of maintaining side control while the other practices an objective of escaping it.

Your understanding of each practice exercise’s effectiveness in supporting a given objective will improve with experience and with research. If you’re just getting started, don’t worry – experiment, take stock, and continue to tweak.

If you’re a veteran, keep challenging your own assumptions, researching different approaches, and being open to testing new things in your lesson plans.

As for the exact structure of a lesson plan, the next sections take a deep dive into two effective types of plan outlines.

Traditional Martial Arts Lesson Plan Templates

The traditional approach to lesson planning is tried-and-true and has produced many great martial artists. One of its high points is that it’s easy to pick up and put together quick plans if you already have a curriculum mapped out. Perhaps even more importantly, it’s easier to train new instructors on how to conduct and design lessons this way.

On the downside, this practice structure can be outdated compared to more progressive templates and often tries to cobble too many unrelated types of curriculum items into one class (e.g., sparring and forms practice) in a way that both domains are neglected.

Traditional lesson plans always follow a similar progression:

- Calisthenic warmup

- Practice of basic kicks and hand techniques (usually in the air or on a pads)

- Curriculum pieces

- Cool down

Children often have games interspersed throughout the lesson as well as a “mat chat” with the instructor on a character or value like confidence or self-respect. So a typical lesson plan is structured like this:

- Warmup

- Basics

- Curriculum A (e.g., forms)

- Water Break

- Mat Chat

- Curriculum B (e.g., one steps)

- Game

- Cooldown/Announcements

For adults, it might look more like this:

- Warmup

- Basics

- Curriculum A (forms)

- Water Break

- Curriculum B (one steps)

- Curriculum C (self-defense techniques)

- Cooldown/stretching

- Announcements

It’s a lot to fit into 50 minutes to an hour, but done with good time management, it does cover a lot of ground.

However, even with classes upward to 90 minutes in duration, it can still feel like there are too many unrelated skills competing for one another for attention during each session (board breaking, forms, one steps, self-defense techniques, sparring, etc.). For this reason, many traditional programs elect to have a separate live sparring class every week.

Modern Martial Arts Lesson Plan Templates

The basic structure and content of these templates is built on what’s called the “constraints-led approach” to motor learning, a framework for skill acquisition that is well-researched and fast gaining adoption by coaches in the sports and martial arts worlds. It’s also based on the idea that practice variability (lots of different exercises within the same session) actually promotes better learning, as opposed to a session that focuses entirely on one concept, technique, strategy, range, or position.

(However, we’ll explore below how you can still have a session focus without sacrificing practice variability.)

With this way of designing lessons, virtually all of the exercises involved are alive. In other words, they have a genuine level of unscriptedness and uncooperativeness between training partners, very much like sparring or a competitive game. Jiu-jitsu people often call this concept positional sparring and strikers sometimes call it technical or scenario sparring.

An important note: This approach to martial arts lessons is meant for sparring-based programs. If you want to teach a competitive forms program, the traditional template, with some adjustments for focus, will be more advantageous for you.

With that said, this is what a typical lesson plan might look like for a martial arts class:

- Warmup game (e.g., fighting for double underhooks)

- Live exercise A

- Live exercise B

- Live exercise A

- Live exercise C

- Rounds of free sparring/rolling

- Cool down/stretching

The template above has a lot of interesting implications for martial arts curriculum development. The way it’s structured, you get to practice in at least 3 different scenarios and yet with the repetition of exercise A, the session still has a focus. They get the best of both worlds: the benefit of drilling down on something as well as the strengths of variable practice design.

In the next session, you could structure class this way:

- Warmup game

- Live exercise B

- Live exercise C

- Live exercise B

- Live exercise D

- Rounds

- Cool down

This structuring practice is known as interleaving, and it works both within a session and between sessions to ensure that you’re not only getting enough variability but also enough repeat exposures to specific positions or scenarios to gain sufficient practice there.

The constraints-led approach to lesson planning is not confined to the above. You could potentially do a class entirely made up of positional or scenario sparring, for beginners who aren’t comfortable with free sparring. Or you could do a class entirely made up of free sparring, for competition or in anticipation of an upper belt test.

Conclusion

If you want to help your students improve, and keep them improving, thoughtful and well-structured martial arts lesson plans are a must. To ensure you’ve created a standout lesson plan, follow this 4 step process:

- Establish a session intention (learning objectives)

- Determine learning outcomes

- Gather practice exercises that support those objectives and outcomes

- Filter out suboptimal exercises and finalize the lesson plan

If you want to improve your martial arts programs while staying within the bounds of classical structure, follow traditional lesson plan templates. If you want to uplevel your sessions into the most scientific format, give the modern or “constraints-led” templates a try.

Happy lesson planning!

Gym management software that frees up your time and helps you grow.

Simplified billing, enrollment, student management, and marketing features that help you grow your gym or martial arts school.